Laura Levis writes: What are the ingredients of a healthy, inclusive society—one that offers its citizens opportunity, happiness, and a positive quality of life? According to Lawrence University Professor Michael E. Porter, models of human development based on economic growth alone are incomplete; nations that thrive provide personal rights, nutrition and basic medical care, ecosystem sustainability, and access to advanced education, among other goods—and it is possible to measure progress toward providing these social benefits.

Porter’s 2015 Social Progress Index (SPI)—released in April and developed in collaboration with Sarnoff professor Scott Stern of MIT’s Sloan School and the nonprofit Social Progress Imperative—ranks 133 countries on multiple dimensions of social and environmental performance in three main categories: Basic Human Needs (food, water, shelter, safety); Foundations of Wellbeing (basic education, information, health, and a sustainable environment); and Opportunity (freedom of choice, freedom from discrimination, and access to higher education). Porter considers the index “the most comprehensive framework developed for measuring social progress, and the first to measure social progress independently of gross domestic product (GDP).”

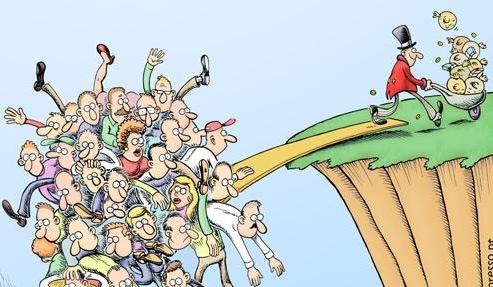

The index, he explains, is in some sense “a measure of inclusiveness,” developed based on discussions with stakeholders around the world about what is missed when policymakers concentrate on GDP (which tallies the value of all the goods and services produced by a country each year) to the exclusion of social performance.

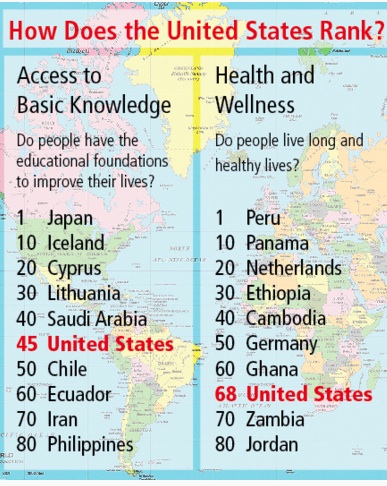

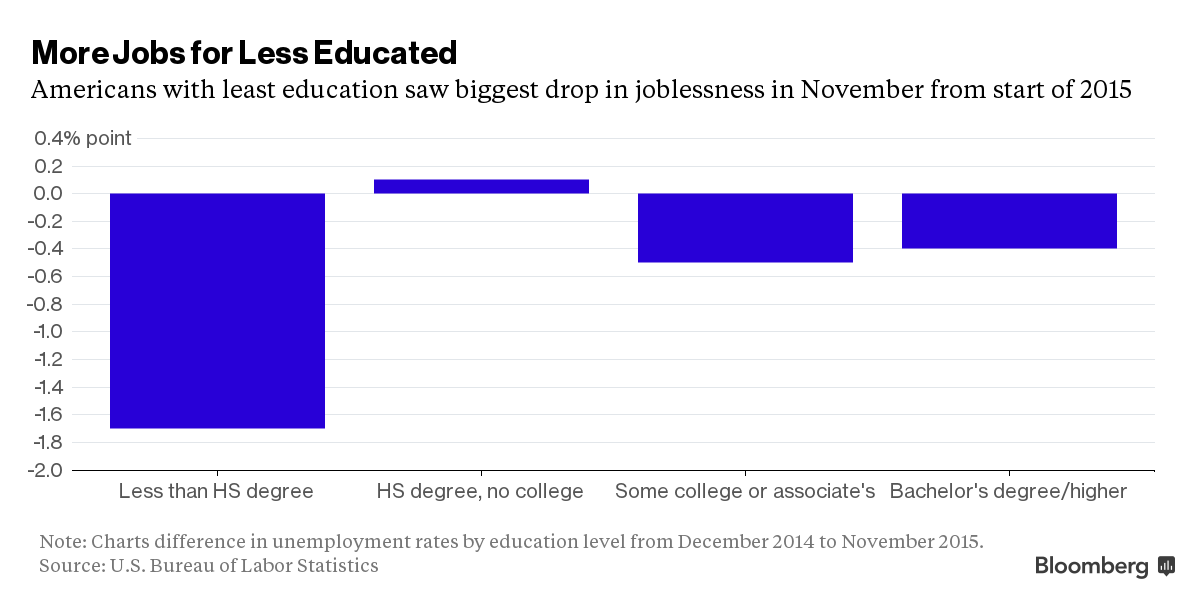

The United States may rank sixth among countries in terms of GDP per capita, but its results on the Social Progress Index are lackluster. It is sixteenth overall in social progress: well below Canada, the United Kingdom, Germany, and Japan in several key areas, including citizens’ quality of life and provision of basic human needs.

About 20 or 30 years ago, for reasons Porter says he cannot completely explain, the rate of progress in America began to slow down. As a society, he points out, Americans slowly became more divided, and important priorities such as healthcare, education, and politics suffered.

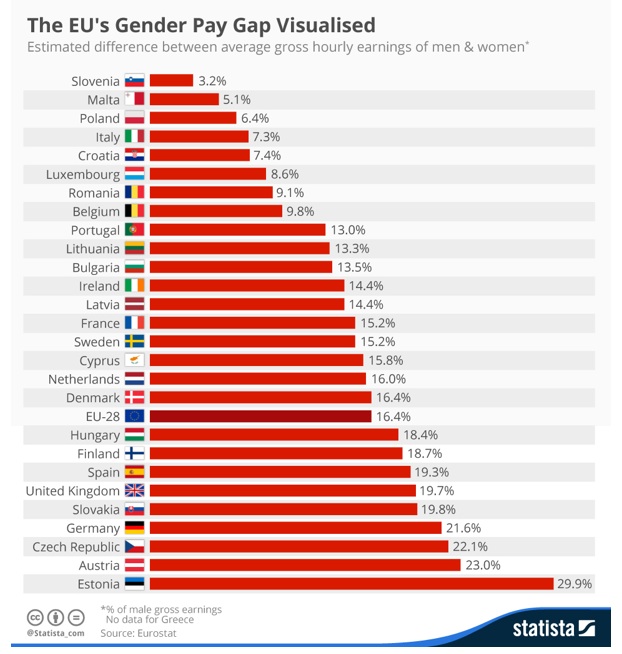

Meanwhile, he notes that even though other fast-growing nations such as India and China haven’t been able to attain a level of social progress commensurate with their economic progress either, certain countries such as Rwanda have “knocked the cover off the ball” in terms of social progress. “They went through a genocide, were devastated, and, to bring the society together, there was a consensus, led by the president, that their first job was to re-energize and restock the society and the capacity of their citizens,” he says. For example, the country achieved a 61 percent reduction in child mortality in a single decade, and today, primary-school enrollment stands at 95 percent. Rwanda also ranks high for gender equity, as women constitute a majority of the parliament—partly he says, because a lot of men were killed, but also because the country set out to be a place where women are not just equals, but leaders.

Porter hopes his continuing work on the index will help explain why the United States is “doing poorly” relative to other countries that are doing well.

In terms of progress for the average citizen, Porter warns, the United States is more threatened now, globally and economically, than it has been in generations.