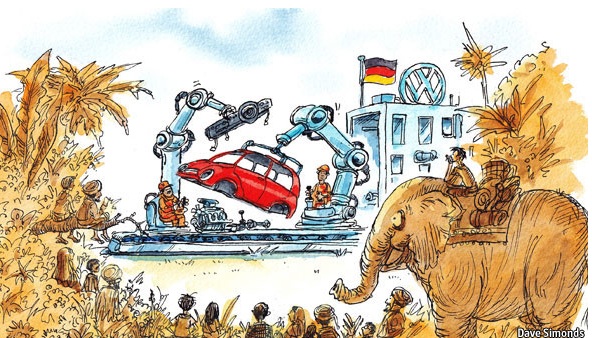

Dhiraj Nayyar writes: India’s central banker Raghuram Rajan is good at asking the right questions. He was one of the few to predict the 2008 financial crisis. He’s now triggered a debate within India over Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s flagship “Make in India” campaign: an effort to boost India’s manufacturing sector to China-like levels.

Rajan questioned whether that should be India’s goal at all. The conventional wisdom is that the only way to find jobs for a young and growing population, and to move workers off the farm and into cities, is to expand India’s export-focused industries. That’s the same route Japan, China and the so-called Asian Tigers all pursued successfully. Yet, Rajan asked, does the world really need another export powerhouse? With demand in developed nations slowing, there simply may not be enough customers for Indian-made goods, no matter how cheap. The alternative — stimulating domestic demand artificially, by raising tariffs on imports — has been tried and failed spectacularly under previous socialist governments.

If one agrees with the goal of boosting manufacturing, the government has yet to offer any convincing strategies for achieving it.

Yet while businesses would happily embrace such changes, they’re unlikely to unleash a manufacturing revolution. Like China, India’s already tried to implement several of these reforms in special economic zones that advertise lower taxes and looser land and labor regulations.

These policies focus too much on symptoms of India’s malaise. The real problem is that markets for four critical inputs for manufacturing, or indeed any business — land, labor, power and capital — are badly distorted. Until the government resolves those distortions, “Make in India” will remain nothing but a slogan.

Consider land. A new land-acquisition law, passed in the dying months of the previous government in 2013, makes buying farmland on which to build factories tremendously complicated and expensive.

On labor, India should have a cost advantage over China, whose labor-intensive goods now flood the Indian market. Chinese wages have risen rapidly over three decades of double-digit growth. India’s haven’t, and almost half the population is still engaged in unproductive agriculture.

Unreliable and expensive power supplies hamper all of India’s businesses.

The issue of expensive capital is one that should particularly exercise Rajan. He knows that India’s closed financial system artificially raises the cost of capital. He’s stuck with a tight monetary policy for the moment because of high inflation. But compared to the rest of the world, Indian interest rates tend to be too high even when monetary policy is more accommodative. There’s also plenty more room for India to open up its financial system.

The government can help manufacturers by following through on pledges to invest in roads, ports and connectivity. But only when India’s markets for land, labor, power and capital work efficiently will the foundations for a true cost-competitive manufacturing revolution exist. Rajan might then find himself a bit more optimistic: Indian companies shouldn’t need any special protections to compete with cheap Chinese goods at home. And when the advanced economies finally recover, there will be other markets to conquer.