Schumpeter has an interesting discussion in the Economist about businesses that pride themselves on contributing to the common good and yet work hard to avoid taxes. He writes; Pfizer has always prided itself on its commitment to corporate social responsibility (CSR). It is particularly proud of the work that it does with NGOs and “other global health stakeholders” to strengthen and improve health-care systems.

This has not deterred it from seeking a gargantuan “tax inversion”. The company intends, as part of a $160 billion takeover of Allergan, to shift its tax domicile from America to Ireland, where Allergan is domiciled, and where corporate-income taxes are considerably lower. Pfizer’s shareholders no doubt rejoiced: in 2014 the company would have saved $1 billion of the $3.1 billion it paid to the US Treasury.

A paper in the January issue of the Accounting Review suggests that Pfizer is far from unusual in trying to perform this pro-CSR, anti-tax straddle. David Guenther of the University of Oregon’s Lundquist College of Business and his co-authors compared the effective tax rates paid by a sample of American firms between 2002 and 2011 with a measure of those companies’ CSR programmes compiled by MSCI, an index provider. It found that the companies which do the most CSR also make the most strenuous efforts to avoid paying tax—and that those with a high CSR score also spend more lobbying on tax.

Surely CSR depends on the idea that firms have an obligation to society, not just to shareholders? And surely the most basic obligation to society is to pay the taxes that support the poor and vulnerable?

Mr Guenther and his colleagues suggest two more intriguing explanations. The first is that companies intentionally embrace CSR for exactly the same reason they try to reduce their taxes—to maximize their profits. Starbucks recognised how much damage its British operation had done to its reputation when the extent of its tax planning was exposed in 2012, and promised to pay around £10m (then $16m) a year in each of the following two years.

The second possible explanation is that companies regard CSR and taxes as substitutes for each other: the less you pay in taxes, the more you have left over for good works.

Rival theories reflect conflicting ideas on what counts as a socially responsible company. The view put forward by various international bodies that seek to set standards for corporate behaviour, and accepted by many big European firms, is that responsible firms should pay a fair share of taxes while privately sponsoring some do-gooding on top of this.

Many CEOs, particularly in America, say the best way for companies to contribute to the common good is to succeed as businesses. Furthermore, they argue, the more money they can keep from the government’s clutches, the more they can invest in new plants (which create jobs in the short term) or research (which creates jobs in the longer term). And the more money they will have left over for good causes as well.

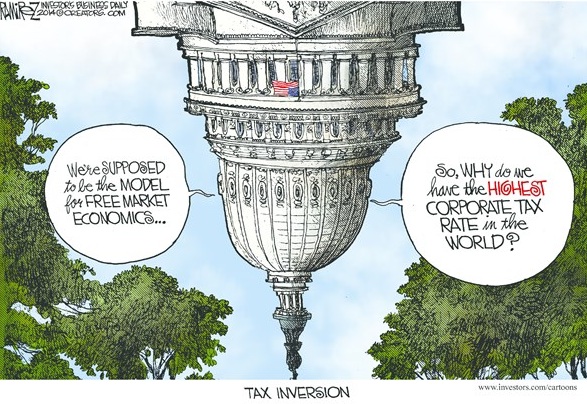

The CEO school of corporate responsibility has something going for it. Such bosses are right to argue that a business’s main contribution to society is to provide jobs and income. They are also right to argue for tax harmonisation: America has only itself to blame if firms revolt against its high corporate-tax rate.