Elizabeth Warren proposes a women’s economic agenda.

“Achieving pay equality for women isn’t enough,” Senator Elizabeth Warren, D.-Mass., said. “We have to make sure that all workers – men and women – are earning enough to live on.”

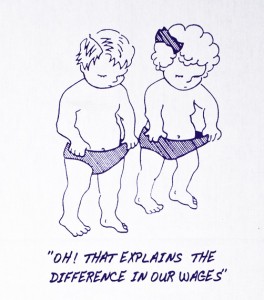

A recent Economic Policy Institute study shows that the gender pay gap has closed some 40 percent. It’s not because women are earning more. It’s because men are earning less.

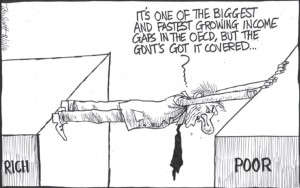

Wages for all workers have been suppressed, because of national policies consciously adopted to guarantee that most of the wealth being created through increased productivity goes to those who are already the richest, most powerful people in America.

It hasn’t always been this way. For decades following the end of World War II, Gould said, pay for the vast majority of American workers went up as productivity rose.

Then economic policies turned against workers. Productivity grew 72.2 percent between 1973 and 2014, but hourly pay for the typical worker rose just 0.20 percent annually. From 2000 to 2014, the gap between productivity and pay grew faster and wider. Productivity rose 21.6 percent but pay increased only 1.8 percent for the typical worker.

If the fruits of higher productivity had been shared with those who had produced the wealth instead of being lapped up by the top one or two percent, Gould said, no one with a full time job would be living in poverty today. Overall, wages would be up 70 percent.

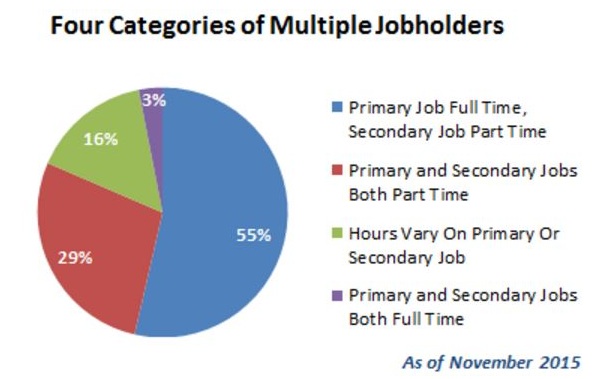

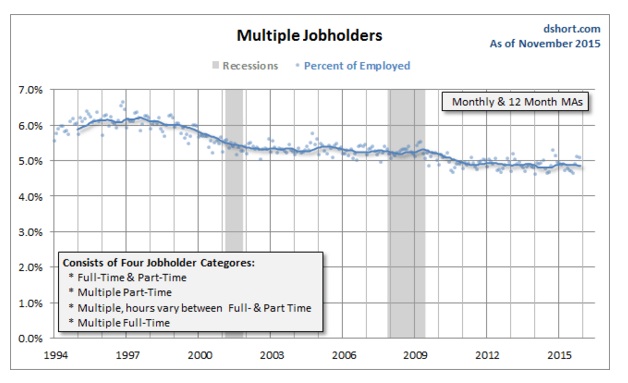

However, because of current economic policies some 35 million working Americans are living in poverty. Many are working two or three jobs.

In presenting the Women’s Economic Agenda, Senator Warren pointed out that more than half of low wage workers are women and that some 14 million children are being brought up in poverty.

“This is an economic issue,” Warren said, “but it is also an issue of American values. No one who works full time should be living in poverty.”

Schedules That Work bill

Warren discussed her Schedules That Work bill. If passed (which is unlikely in today’s Republican-controlled congress) it would prevent employers from calling workers in at the last minute. It would also stop managements from calling workers in, deciding they aren’t needed and sending them home without pay.

“Women especially need some control over their work schedules,” Warren said, “because a large number have sole responsibility for children. How can you plan for childcare if you don’t know what your schedule will be day to day?”

“Congressional representatives such as myself,” DeLauro said, “can take off as many days as we want to. Yet, one quarter of all workers have been fired or threatened with being fired for taking just one day off to take care of their kids.”

Women’s Economic Agenda

EPI’s economic agenda for women addresses the issues Sen. Warren and Rep. DeLauro discussed. It calls for equal pay that’s also a living wage. It stresses the importance of fair scheduling and paid family and medical leave.

“Women in unions are more likely to be paid higher wages and have access to needed benefits and protections. When unions are strong, those benefits and protections spread to nonunion workers as well.”

The agenda also calls for raising the minimum wage for all workers and eliminating the subminimum wage; the nation must protect and strengthen Social Security and pensions.

The agenda ends by calling for national monetary policies that “prioritize wage growth and very low unemployment.”