Global finance leaders believe China will weather its slowing growth and manage a successful transition from an export to a consumer economy despite a huge buildup of internal debt in the world’s second largest economy.

The International Monetary Fund believes the Chinese economy will grow 6.8 per cent this year and 6.3 per cent in 2016, slower than recent levels but still enough to keep driving global economic growth when other positives have largely disappeared.

French Finance Minister Michel Sapin is among the optimists, along with Britain’s George Osborne and IMF chief Christine Lagarde.

China’s Deputy Central Bank Governor, Yi Gang, was keen to reassure his peers at this week’s IMF meetings in Lima, saying a recent devaluation was a one-off and that China’s economy was stable.

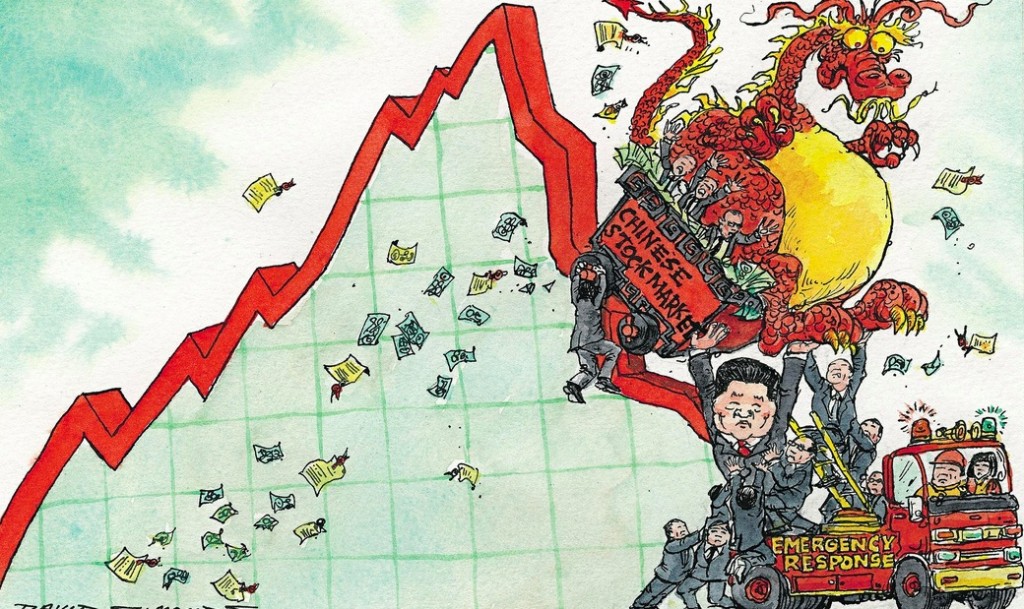

Yet cracks are already appearing in China, an economy whose red-hot growth of almost 10 per cent a year for 30 years fueled a commodity super-cycle that in 2008 pushed oil prices as high as $145 a barrel, and inflated demand for iron ore and edible oils, as well as industrial goods from advanced economies like Germany.

It is not just China that is a risk – although it is by far the biggest one to the relatively rosy IMF forecasts of global economic growth of 3.1 per cent this year and 3.6 per cent in 2016.

In Germany exports to China, Brazil and Russia account for 3.4 per cent of gross domestic product, according to investment bank Barclays, a risk for Europe’s largest economy. China alone accounts for 10 per cent of Germany’s auto exports.

A sharp drop in German exports in August, which fell at their fastest pace since the 2009 financial crisis, is likely to be related to the fall in trade in Asia, Barclays said. Industrial production and factory orders also declined.

“Because of China’s weight in global production and trade, and because of the high commodity intensity of its production and demand, China’s recession is the one that matters most for the global economy,” Citi’s chief economist Willem Buiter has warned.

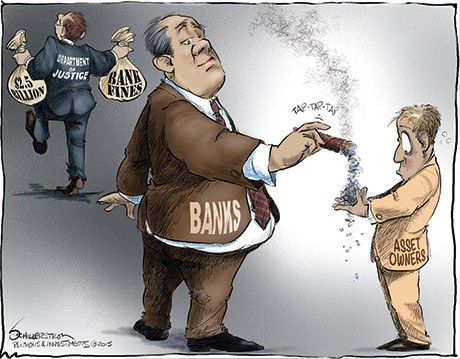

The IMF Global Financial Stability report said that over-borrowing by Chinese companies was equivalent to a quarter of gross domestic product.

While China’s August stock market crash and sudden devaluation rattled global markets, it may have just been a foretaste of things to come if China does not address its huge debt problems.

“Direct financial spillovers include a possibly adverse impact on the asset quality of at least $800 billion of cross-border bank exposures,” the IMF report said.

It calculates that if a tightly wound credit cycle in emerging economies, including China, unwinds with rising corporate default rates, aggregate global output could be as much as 2.4 per cent lower by 2017 relative to the IMF’s baseline forecast.

“China still has policy buffers to absorb financial shocks, including a relatively strong public sector balance sheet, but over-reliance on these buffers could exacerbate existing vulnerabilities,” the IMF said.