Will what worked in Georgia work in Ukraine? It will if it is up to Davit Sakvarelidze, deputy prosecutor general of Ukraine and the chief prosecutor of the Black Sea city of Odessa.

L. Todd Wood writes: Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko has brought in veterans of the country of Georgia’s reform process to help Ukraine remove the legacy of decades of Soviet and oligarchic corruption. Sakvarelidze, appointed to the national post in February 2015, and to the Odessa post several weeks ago, is attempting to bring change to the one state organization that has most resisted the political reforms sweeping the country, the General Prosecutor’s Office, which enjoys very low trust among the Ukrainian people – indeed, for good reason. I sat with Sakvarelidze last week, during a visit to the Academy of Prosecutors in Kyiv, to discuss the challenges ahead of him. The place was teeming with young, energetic applicants making their way through the new selection process. There seemed to be a pervasive, youthful motivation, albeit possibly naive, with the people I met while engaged at the facility.

Along with former Georgian Prime Minister Mikhail Saakashvili and others, Sakvarelidze is working to bring trust in government to the Ukrainian people.

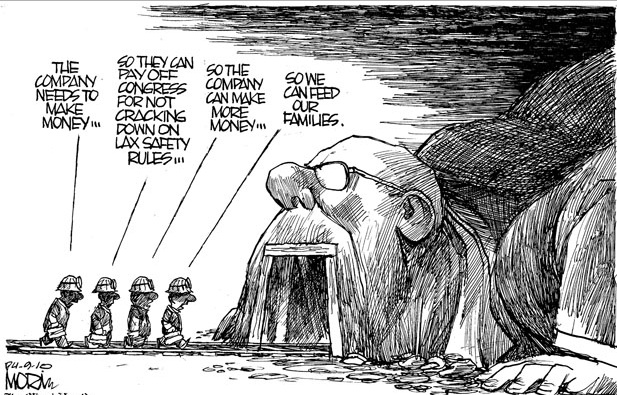

Sakvarelidze is attempting to overhaul the General Prosecutor’s Office and remold it into a professional force that can deal with the sickness destroying Ukrainian society. The number of prosecutorial positions have been reduced significantly and all candidates, even current hires, must undergo rigorous testing and training to be accepted into the new reality. More than 700 positions must be filled.

The entire effort is behind schedule. In fact, the newly created National Anti-Corruption Bureau cannot begin its work until the prosecutor’s office is up and running. Yet Sakvarelidze is optimistic and seems determined.

“Political changes have reshaped the political structure, but the Prosecutor General’s Office has not changed; the system has remained the same. Now we are trying to correct it,” he recently said at the 12th Yalta European Strategy Annual Meeting in Kyiv.

Regulatory reform should also be a big part of the anti-corruption effort, according to Sakvarelidze; the ability for bureaucrats to siphon cash from the public needs to be reduced. In Georgia, the time needed to get a new passport was reduced to 60 minutes.

The stakes for Ukraine are huge. There have been many half-baked anti-corruption campaigns in the past that lacked the political will for real reform. This time Sakvarelidze hopes it’s different. “It is not just Ukraine who will feel the pain if we fail. Ukraine is the gateway to Europe, a wall against the tide of Soviet-style corruption. I’d hate to think of the consequences to Europe and the world if we fail.”