By Yasmine Motarjemi and Caroline Hunt-Matthes /Verfassungsblog

In April 2019, the European Parliament adopted the Whistleblowing Directive, which aims to protect whistleblowers in European Union (EU) countries. The directive entered into force on 16 December 2019 and EU Member States have until the end of 2021 to transpose the provisions of the directive into their legal systems.

Although the EU Directive represents a quantum leap in whistleblower protection, it nevertheless has some important shortcomings that undermine its potential. The recommendations in this text are based on the authors’ personal experience as whistleblowers: Yasmine Motarjemi was Corporate Food Safety Manager by Nestlé. In the framework of her work she reported mismanagement in food safety. Subsequently, she experienced severe retaliation and was dismissed in 2010. Since then she is in legal battle with the company (for further information, see here). Caroline Hunt-Matthes’ has served as a UN peacekeeper and United Nations staff member for over a decade and is the only vindicated United Nations whistleblower to receive an apology in the longest litigation in UN history (15 year).

- The need for considering transnational threats.

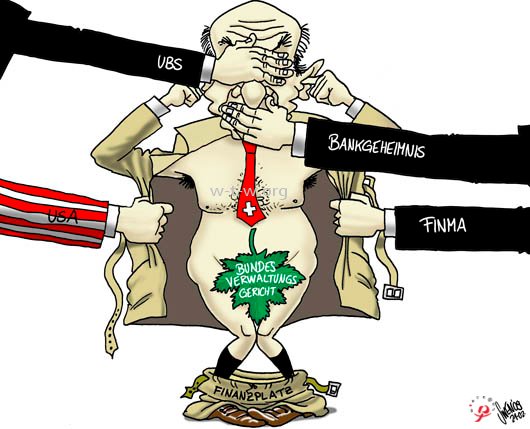

Contrary to the progress made in the European Union for the protection of whistleblowers, after 12 years of debate, in March 2020, Switzerland buried its draft proposed law. No new initiative is in sight. We need to realize that, given the globalized nature of the modern world, the lack of whistleblower protection in Switzerland, which is home to the highest concentration of Fortune Global 500 multinational corporations is a threat to the interests of other countries. It undermines the benefits that European countries hope to achieve by the EU Whistleblowing Directive. Unfortunately, the European Directive does not address the question of whistleblowers in countries where there is no law for their protection. This is, for instance, of critical importance in the case of employees in multinational companies based in Switzerland or employees of international organisations, where policy and decisions taken in the head office of these companies or organisations have global implications. To address such a problem it is recommended that protection and judicial assistance is also extended to employees of multinational companies who also operate in the EU countries. Please see also here.

- The need to consider the miscarriage of justice within the scope of the law

This is a core issue in protecting whistleblowers and addressing their objectives, i.e. defending public interest. A law is rendered effective only when it is properly implemented. The corollary is that the violation of the law must be sanctioned. Short of this, the law would be futile. Hence, the protection of whistleblowers requires both a comprehensive law as well as a robust, reliable and independent judiciary to implement the law. These should work hand in hand. Regrettably, the judicial system is all to often the weak link in the protection of whistleblowers. Our experiences as whistleblowers are cases in point. They are given here to show, as examples, the reality of many whistleblowers and potential loopholes in the system.

As required by the EU Whistleblowing Directive, Yasmine Motarjemi’s former employer, Nestlé, had an internal whistleblowing system since 2005. For more than four years (2006-2010), she reported food safety mismanagement and severe retaliation to all levels of management. All to no avail. The Nestlé management refused to examine the food safety management concerns. Only after 3 years, Nestlé conducted a disingenuous inquiry into Ms Motarjemi’s complaints of bullying and harassment. The failure by Nestlé to take action on her internal reports led to serious food safety incidents across the world and brutal retaliation against Ms Motarjemi for essentially doing her job. It took her 10 years to hold Nestle to account in Swiss court for retaliation. In spite of a favorable judgement, there have been no sanctions, no disciplinary measures, nor examination of her food safety complaints, and so far no redress.

During the court proceedings, Nestlé witnesses perjured themselves in court and acted with contempt towards the judicial system. A situation that demonstrated the need for a robust and independent judicial system vis-à-vis a powerful multinational corporation. The fact that the protracted judicial proceedings continued for ten years prevented closure of the case, preventing Ms Motarjemi from moving on with her life and returning to the world of work. All of these factors, together with the burden of the costs of a protracted lawsuit, pose a serious deterrent for employees or citizens who wish to bring forward information of public importance.

The lack of a well-functioning judicial system is not specific to Switzerland. Citizens of many countries report similar problems in their respective countries. In the course of their quest for justice, many citizens are confronted with situations of conflict of interest, nepotism, misinterpretation of the law, corruption, false medical examinations, deceitful lawyers, disingenuous and non-independent investigations, misleading facts or half-truths, defamation of character etc. The situation is such that in some jurisdictions the judiciary, the body that plays a key role in the enforcement of any law including whistleblower protection law, itself suffers from dysfunctions. Therefore, it cannot efficiently and adequately protect whistleblowers, especially those who are confronted with multinationals or powerful entities. A law on whistleblowing is not sufficient for protection of whistleblowers; the question to address is also the procedure for a fair independent investigation and redress.

Lip service is often given to the investigation process by those who control the investigation process as opposed to a rigorous and independent investigation conducted by an independent entity. This was the central issue in the cases of Hunt-Matthes v The United Nations 2013. United Nations judges determined that the United Nations Ethics Office failed to provide protection to Ms Hunt-Matthes who reported through official UN channels corrupt practices within the Inspector General Office of the UN refugee agency (UNHCR). Of all cases regarding whistleblower protection that were judicially reviewed by UN judges errors were found in 100% of cases, i.e. whistleblowers were not properly protected.

Moreover, the United Nations litigated for 15 years against Hunt-Matthes – the longest retaliation case in UN history which concluded in settlement and apology by UNHCR. Again, no accountability was enforced despite the judges’ request.

In view of the above, in the context of whistleblower protection, particular attention should be paid to the functioning of the judicial system. Fundamental procedural flaws, including gag orders and SLAPP (strategic lawsuit for public participation) which prevent a fair and speedy trial, must be examined and corrected. Fast track judicial procedures should be considered. Breach of whistleblowing law should be categorised as a criminal offence, as it has the potential to stifle critical information of public interest. Sanctions should be dissuasive. Highly important, the scope of whistleblowing law should include miscarriages of justice and their underlying factors, that is the issues that derail the proper functioning of the judicial system. To this end, proper protection should also be extended to citizens who report such failures.

Another essential element of the scope of the whistleblowing law should consider breaches of the whistleblowing law itself, that is retaliation in form of bullying and harassment. Such practices set a poor company culture where employees would feel too intimidated, or even threatened, should they report wrongdoing through official channels. A fear-based company culture is detrimental to risk management and undermines the objectives of the whistleblowing law. The underlying organization culture is an aspect which underpins successful “speak up” work cultures.

- The size of establishments.

The European directive requires companies of above 50 employees to set up an internal whistleblowing system. Such a limitation is arbitrary. In the industrial age, where robotics and artificial intelligence are gradually entering our production system, a company may be able to achieve, with few staff, a high production output. The supply chain is also complex and an ingredient produced by a small company can subsequently contaminate a large number of different products. Start-up companies with small workforces may produce products, materials, science or technologies that may pose public health risks. The same goes for scientific institutions. Fraud or malpractice in the scientific field will lead to false scientific information that is highly deleterious for society. Some companies may also decide to work with subcontractors, volunteers, temporary staff, etc. to keep their formal numbers of staff low and flexible. An internal whistleblowing system should be part of the internal control system of any business or institution. Small businesses or organisations may make use of an external independent provider.

- The time span for reporting, investigating and corrective measures.

The 7-day time limit for acknowledging receipt of a report and then 3 months for follow-up is too long for certain types of violations, such as those relating to public health or environmental issues. The emergence of the coronavirus epidemic demonstrates the importance of speed of reporting and action in matters of public health. In food or pharmaceutical companies, reported problems are usually acknowledged within hours and concrete measures are taken within 24 hours. Therefore, the time allowed for feedback and corrective measures should be sector-specific. This time frame should be as short as possible, so that corrective measures are implemented before the public is harmed or damage is at least minimised. The burden of proof that action has been taken within a reasonable time to protect whistleblowers and the interests of the public should rest with the company/organization. Guidance is also needed how to investigate retaliatory measures, in particular the role that the management has played.

- Records and responsibilities

A major omission from the Directive is the requirement to keep records, such as notes of meetings and decisions taken as well as the definition of the roles and responsibilities of senior management. When wrongdoing occurs, it is important to have an accurate record of events and corrective actions taken, and also to be able to identify those responsible for decisions. In Ms Motarjemi’s experience, her former employer’s response in the court was a cacophony of inconsistent statements, with each manager contradicting the other and shifting the responsibility on each other.This is a central characteristic of denial culture. The management of Nestlé acknowledged that managers in their company did not have job descriptions defining their responsibilities. In such a situation, one wonders how the system can identify and sanction the person(s) responsible for the wrongdoings?

- Independent implementing agency.

The experience of whistleblowers indicates that the system of protection will be more reliable if an independent regulatory agency is responsible for implementing the law, that is, inter alia, receiving and assessing reports from whistleblowers, advising them, investigating their case, providing judicial assistance, liaising with other competent authorities for implementing corrective actions, communicating with media, or taking any other necessary actions. In particular, it would be important to monitor successes and failures and analyse their causes with the aim of improving the system of protection.

- Learning from the experience of whistleblowers

Studying the experiences of whistleblowers can provide valuable information about the barriers that whistleblowers encounter and eventual loopholes of the system. This can be useful for tightening the gaps and designing an effective whistleblowing system. For instance, the decade long failure of whistleblower protection in the United Nations between 2006 and 2016 merits study. It resulted in the abolition of the old UN policy under the incoming UN Secretary General and the creation of a new policy in 2017. According to UN inspectors the failure of UN Ethics Offices to properly protect bona fide UN whistleblowers from brutal retaliation has created a culture of silence. Consequently, the mandatory requirements to report misconduct is failing.

Whistleblower Protection in Europe- How to Make it Effective?

www.greens-efa.eu/en/article/news/whistle-blowers-directive/

Make Taxes Work For Women

Make Taxes Work For Women

Rachel Woolley reports: What is a PEP, and why should financial institutions be vigilant when assessing the risk of doing business with one? What if someone is not a PEP, but an individual that happens to be associated with one through family, business or other close personal connections? Is Kanye West now a PEP?

Rachel Woolley reports: What is a PEP, and why should financial institutions be vigilant when assessing the risk of doing business with one? What if someone is not a PEP, but an individual that happens to be associated with one through family, business or other close personal connections? Is Kanye West now a PEP?